"Suppose your Great Father wanted your lands and did not want a treaty for your good; he could come with 100,000 men and drive you off to the Rocky Mountains."

"Suppose your Great Father wanted your lands and did not want a treaty for your good; he could come with 100,000 men and drive you off to the Rocky Mountains."

Luke Lea, U.S. negotiator, Treaty of Mendota, 1851

1805: In 1805 the Dakota ceded 100,000 acres of land at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. U.S. Army Lt. Zebulon Pike negotiated the agreement so the U.S. government could build a military fort there. Of the seven Indian leaders present at the negotiations, only two signed the treaty.

Pike valued the land at $200,000, but no specific dollar amount was written into the treaty. At the signing, he gave the Indian leaders gifts whose total value was $200. The U.S. Senate approved the treaty, agreeing to pay only $2,000 for the land.

Generally, the Indians who signed treaties did not read English. They had to rely on interpreters who were paid by the U.S. government. It is uncertain whether they were aware of the exact terms of the treaties they signed.

Generally, the Indians who signed treaties did not read English. They had to rely on interpreters who were paid by the U.S. government. It is uncertain whether they were aware of the exact terms of the treaties they signed.

Minneapolis and St. Paul are located on land ceded in 1805.

1825: The U.S. government arranged the Prairie du Chien treaty between the Dakota and Ojibwe, as well as the Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Sac and Fox, Iowa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa tribes. The treaty set the boundaries of tribal land. After that, it was simpler for the government to negotiate with the Indians for the purchase of their lands.

1837: At Fort Snelling in 1837, the Ojibwe ceded their land north of the 1805 area to the U.S. government in exchange for cash, the payment of claims made by traders, and annual payments of cash and goods, or annuities.

Later that year, a group of Dakota leaders was brought to Washington, D.C., having been told that they would be negotiating the settlement of their southern boundary. Instead, they were pressured into ceding all their land east of the Mississippi. The land was valued at $1,600,000, but the U.S. government agreed to pay far less. The Dakota were promised the interest on $300,000, invested at 5 percent. This amounted to $15,000 per year. The government kept control over one-third of this money, reserving (but not allocating) it for education. Another $200,000 was paid to friends and relatives of the tribe and to settle debts, and $16,000 was given to the Dakota leaders as an incentive to sign the treaty. Each year for 20 years, $23,750 was allocated for annuity payments, food, education, equipment, supplies, and government services.

1847: In 1847 the Ojibwe ceded land for Ho-Chunk and Menominee reservations. This land is west of the 1837 sale. The Ojibwe received $17,000 in cash for the land and the promise of $1,000 annually for the following 46 years. The Ho-Chunk and Menominee reservations were never established.

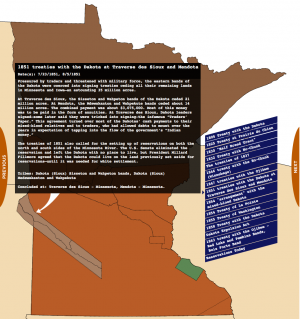

1851: Minnesota became a territory in 1849. White settlers were eager to establish homesteads on the fertile frontier. Pressured by traders and threatened with military force, the Dakota were forced to cede nearly all their land in Minnesota and eastern Dakota in the 1851 treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. At Traverse des Sioux, the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Dakota ceded 21 million acres for $1,665,000, or about 7.5 cents an acre. Of that amount, $275,000 was set aside to pay debts claimed by traders and to relocate the Dakota. Another $30,000 was allocated to establish schools and to prepare the new reservation for the Dakota.

The U.S. government kept more than 80 percent of the money ($1,360,000), with only the interest on the amount--at 5 percent for 50 years--paid to the Dakota. The terms of the Mendota treaty with the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands of the Dakota were similar, except that those payments were even smaller. The treaties of 1851 also called for setting up reservations on both the north and south sides of the Minnesota River. But the U.S. Senate changed the treaties by eliminating the reservations and leaving the Dakota with no place to live. Congress required the Dakota to approve this change before appropriating desperately needed cash and goods. President Millard Fillmore agreed that the Dakota could live on the land previously set aside for reservations, but only until it was needed for white settlement.

1854: The arrowhead region of northeastern Minnesota was purchased from the Ojibwe. Three small reservations were located on parts of this land.

1855: The Ho-Chunk ceded their land in Minnesota, except for one small reservation in the southeastern corner of the Territory. The Ojibwe ceded land in north-central Minnesota. Nine reservations were created on this traditional Ojibwe land.

1858: A month after Minnesota became a state, a group of Dakota traveled to Washington, D.C., to discuss their reservation. The Dakota were pressured to cede the lands on the north side of the Minnesota River. They received 30 cents per acre, estimated to be only about 5 percent of the land's value. When the funds were finally distributed in 1860, most of the $266,880 promised went to pay debts claimed by traders.

By 1858 the Dakota had only a small strip of land in Minnesota. Without access to the land upon which they had hunted for generations, they had to rely on treaty payments for their survival. The inadequate money and goods often arrived late. By summer 1862, most of the Dakota were starving--one of the causes of the U.S.-Dakota War, which lasted six weeks. Nearly 400 Dakota men were tried by a military commission, and 303 were sentenced to death. President Lincoln pardoned many, but 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato. The remaining Dakota were sent to prison in Iowa or to reservations at Crow Creek in what is now South Dakota, and at Santee in Nebraska Territory.

In 1863 the Dakota were forced to give up all their remaining land in Minnesota, and the U.S. government canceled all treaties made with them. The Ojibwe reluctantly ceded most of their remaining land in northwestern Minnesota in treaties of 1863, 1864, and 1867. In 1871 Congress ended the practice of making treaties with Indian nations. However, past treaties remained in place.

Kaplan, Anne R., and Marilyn Ziebarth. Making Minnesota Territory, 1849-1858. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1999.

Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Websites

Tales of the Territory. Minnesota Historical Society.

Treaties with Minnesota Indians

Minnesota Humanities Center Treaties Project

Primary

Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties.Vol. II. Compiled and edited by Charles J. Kappler.Washington:Government Printing Office, 1904.Oklahoma State University Library.